Written by Rachel Davis: Design Research Team Lead for the Trademark Licensing Team

University of Toronto’s Trademark Licensing Department began their partnership with the Innovation Hub in the Summer of 2018 to better understand the ways in which a sense of school pride can be fostered in the lives of students. During this previous partnership, themes such as “survival” and “fragmentation” emerged from the research to describe students’ perception of the university experience. The Innovation Hub continued this partnership during the 2018-2019 academic year to expand on these themes and to better understand student pride at U of T.

During data collection, the Trademark Licensing team began interviews by asking research participants to share their “U of T story”. From the previous research project on perceptions of U of T, we could predict that inquiring about school pride directly would lead to a discussion about “surviving” a “fragmented” but “prestigious” institution. So, to gain a deeper understanding that would be situated in daily life, we asked students (in 1 hour interviews) to simply share whatever came to mind about their time at university. This approach made analysis somewhat daunting, where researchers analyzed data ranging from the miscellaneous narrations of students’ best and worst moments, to their typical routines as a student. This inquiry into school spirit necessitated a comprehensive perspective of the student experience.

For simplicity, we grouped analysis into four spheres of student life: Academic, Social, Wellbeing and Future. By reviewing the data through this lens we noticed students’ belief that they must sacrifice some aspects of their life to survive university. New students were prepared to give up hobbies, sleep, and everything they used to enjoy, but soon found themselves caught in an irreconcilable conflict. Spending too much time on Academic pursuits can leave a student feeling burnt out and uninspired. At the other extreme, if building a sustainable lifestyle takes up all of a student’s time, they may not be making the most of the Academic learning experience they are paying for. Students began to realize they needed to find balance to truly feel successful, and as they struggled with this daily, concerns about the Future haunted them but were often unaddressed. In the Future sphere, more tensions came up: for many it seemed impossible to reconcile what they love with what seems viable.

Within the academic sphere, student narratives around “smart”ness and “failure” stood out. One of the strengths of collecting narrative data is its efficacy in revealing the shared language students use to communicate and the mindsets with which they evaluate themselves and each other. After hearing yet another student confess to me “I’m not smart”, I began asking interviewees what they meant by this. The responses were consistent. Something like :

“It takes time for me to learn a new concept. I don’t get it right away like everyone else seems to- I actually have to study!”

Anthropologist Karen Ho coined the term “Culture of Smartness” to highlight the narrative that is impressed upon students at schools such as Princeton and Stanford during recruitment season for Wall Street investment banking. She notes that her informants were often expected to work 100 hour work weeks, but as they adjusted to their new roles, they began to “claim hard work as a badge of honor and distinction”. In that setting, “smartness” shaped the institutional culture by inciting young people to work beyond the point of exhaustion and feel overconfident in the merit of their decisions. Meanwhile, at University of Toronto, the outcome was that students began to internalize their failures (“I’m not smart”) and downplay their successes (“That midterm was easy”).

Another repeated phrase was “I am going to fail”, so we began to reflect on the implications of living with the threat of failure. It was impossible to consolidate a single definition of failure, considering it could mean something different depending on each student’s goals. This failure can manifest itself as grades that are drastically different from high school, grades that will unlikely be high enough to get into graduate school, or not meeting the cut-off to get into an academic program. Or, it can mean literal failure: getting an F on one’s transcript! It is inevitable that at some point students will fail to live up to the expectations they place on themselves. While individual expectations may vary, students were usually not exaggerating when they expressed the precarious reality of living with the threat of “failure” that they will not be able to recover from. While each student may define “failure” differently, it is inevitable that students will at some point fail to live up to their expectations of themselves as they adjust to university expectations. Rather than understanding that academic setbacks are inevitable, they perceive failure as unthinkable and are not prepared to face it or talk about it.

Over time, students began to build strategies to cope with pressure and find time for basic self-care. Students recognized the need for naps, breaks, and mindfulness to escape from daily life. This attempt to resolve the conflict between education and personal life lead to a complicated relationship with time: students were hyper aware of the passage of time, felt guilty when they were not working, and felt the need to justify how fitting hobbies and healthy activities into their schedule will improve their academics. It is worth noting that when students encountered challenges in various areas of life, they first looked to themselves to solve the problem. This self-reliance led them to explore personal strategies before seeking help from their support system or professionals. This situation is intensified by the “smart”ness narrative. One of our participants was an administrator who commented that “the smart kids who have always had 90s…are often not equipped” with the self-advocacy skills necessary to access resources in a bureaucratic environment. Furthermore, the “self-care” narrative can have dangerous implications here. While it is helpful to raise awareness for the fact that mental health can affect us all at some point in our lives, self care has become popularized as a way to avoid experiencing mental health challenges, especially in environments where burnout is common. These narratives that aim to reduce the stigma around mental health must be careful not to erase mental illness and the existence of professional help in the process. While self-care can help people cope with stress and poor mental health, it will not treat mental illness. Furthermore, if the self-care narrative implies that self-care is adequate, students with mental illness and/or in crisis may blame themselves for failure to feel better, and not feel encouraged to access resources.

Lastly, U of T students perceive themselves to be alone. Even the most well-connected students described the solitude of daily life on campus (“you walk to school by yourself, you sit in class by yourself, you go to the library by yourself…”), and when they faced academic setbacks, they believed they were the only ones struggling. When dealing with mental health challenges, they felt encouraged to know that their peers and mentors have felt the same way.

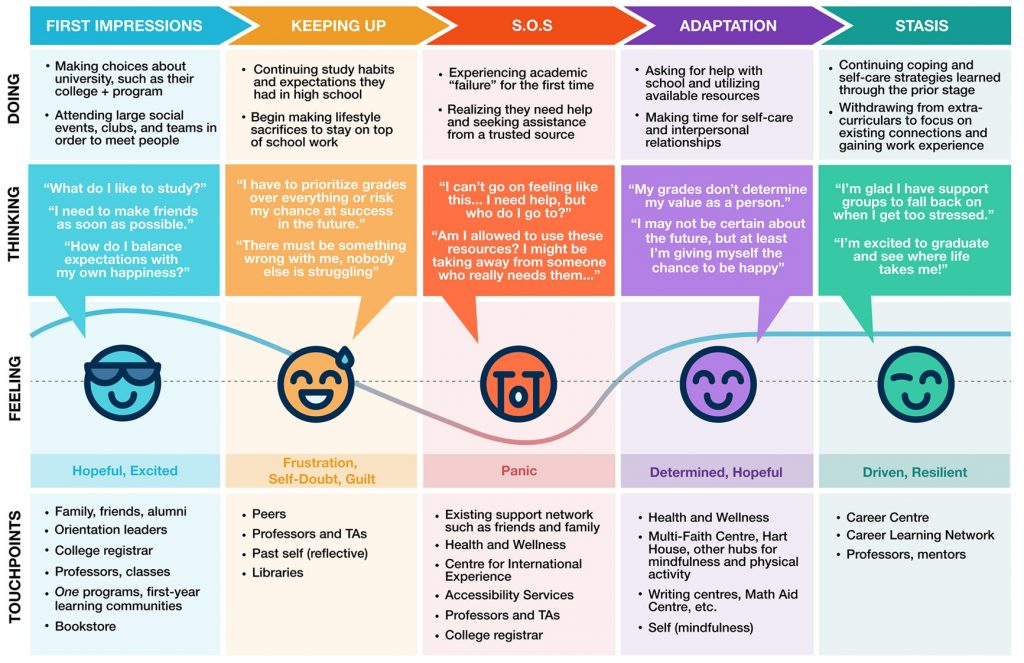

These findings were realized through authentic student stories, which were captured in three personas in the final report. By understanding their lived experiences, we were also able to develop a journey map which visualized the stages that a student may feel during their education by addressing their touch points, feelings, their thinking in the situation, and what they did to either understand how they felt or learned to move forward.

This research at the Innovation Hub contextualized some of the implications for institutional pride that current U of T students face – from the insights and themes, it seemed that those who achieve balance are most likely to feel a sense of pride in the university. This is especially true if students did not overcome adversity they faced on their own, and felt supported and listened to in times of crisis. Through proposed next steps and considerations for how U of T can support these spheres of student life, the Innovation Hub hopes that this will help individuals to empathize with student needs, the barriers that exist, and the overall experience of being a U of T student.

To inquire about the Trademark Licensing report or to learn more about the Innovation Hub, please contact Julia Smeed at julia.smeed@utoronto.ca , by phone at 416-978-8619 or by completing the contact form at here.

0 comments on “Spotlight: Trademark Licensing and Student Pride at U of T”