Curiosity is a powerful tool for navigating how we interact with the world around us. In this blog, Manuela reflects on how she stays curious in her own life to broaden her own understanding of people and information, and the impact that acting with curiosity can have on ourselves, others, and the world.

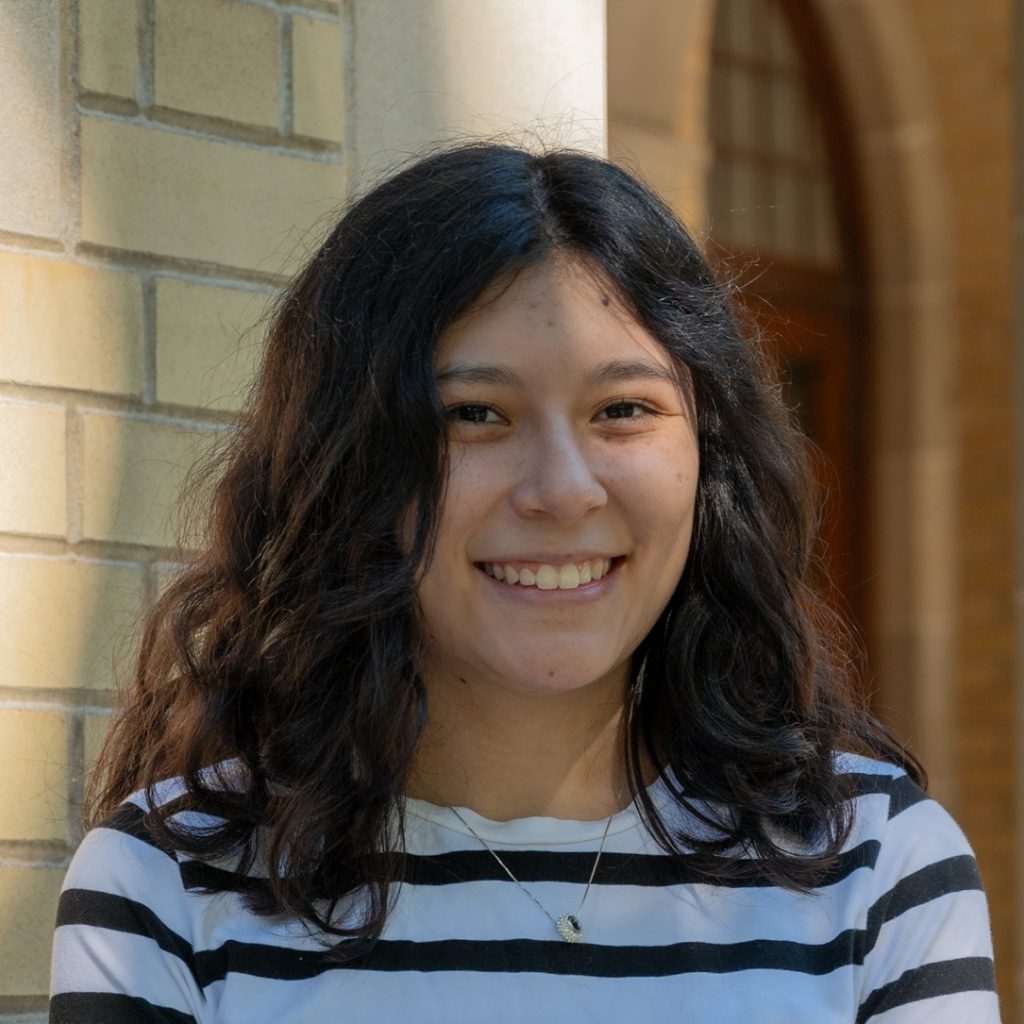

Written by Manuela Mora Castillo, Blog Editor & Content Writer, Honours Bachelor of Arts, Political Science and History Double Major, Latin American Studies Minor

When I attended the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) last semester, I was extremely excited about the opportunity to interview film directors, producers, and cast members. I was eager to ask César Augusto Acevedo, the director of Horizonte (2024), questions about the movie’s concept, historical references, and the inspiration behind such a beautiful film. Yet, when it was time for the Q&A session, as multiple audience members began raising their hands, I started to worry that my questions were not smart enough to ask. Pushing past my nerves, I raised my hand to asked my question, and I left feeling satisfied knowing that the director’s response had given me an angle to write my review of the film.

This experience taught me the value of curiosity. Ever since primary school, I have been taught the importance of asking questions, even if they may not seem valuable at first. I always assumed that the courage to ask for clarification only applied to the classroom, but sitting in that theater, I realized this was far from the truth. I’ve since realized that curiosity plays a much bigger role in how I understand the world, and it is essential in getting me to ponder, evaluate, and examine my overwhelming doubts.

Big Questions: A Path to Innovation

One of the most obvious impacts of curiosity is in innovation, where world-altering projects often start with small, unassuming questions. A few years ago, my high school teacher introduced me to the story of Rosalind Franklin, a British scientist who was instrumental in the study of DNA. At the time, Franklin was conducting research on DNA at King’s College London when she developed Photograph 51, an X-ray picture of a DNA strand. This image, along with her extensive data, inspired James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins to discover the double helix structure of DNA.

To me, Franklin’s story is a perfect example of what curiosity can do. By asking multiple questions, her research led to breakthrough revelations in science that broadened our understanding of the world. At its core, the process of asking questions and pursuing the unknown helps us consolidate new paths for research, as unsolved inquiries highlight the areas in need of further investigation. When questions require answers, curious people design their own course to navigate these uncharted waters.

Curiosity of Experience

With my academic background, it was hard for me to conceptualize curiosity as more than a fundamental research value, which all great scientists and analysts need to have if they wish to succeed. When I joined the Innovation Hub, I was pleasantly surprised to realize that curiosity transcends our traditional understanding of research. Our design research teams collect student feedback throughout their data collection processes and engage in conversation with members of the U of T community. Teams often start the process by asking a big question and letting participants pave the path. By examining the stories with an open mind, our design researchers’ curiosity and interest in participants’ well-being help uncover students’ needs and identify the varying strategies to address them.

Yet, as the Innovation Hub reminded me since day one, curiosity is not merely about asking questions, or about wondering what people want. Rather, it focuses on inquiring about people’s experiences—their day-to-day routine, their likes and dislikes, and the prevalent interactions in their life. It is these seemingly ordinary activities that truly highlight the necessity for change, ensuring that curiosity leads to new discoveries and understandings, such as wondering why people might need to innovate in the first place.

Curiosity Builds Empathy

This approach to curiosity reminded me that by learning about other people’s lived experiences, we can broaden the audience that benefits from innovation. After all, needs are not always explicit—or as evident as the missing DNA structure—and it is a curious person’s duty to pinpoint concerns that others themselves might not recognize. To do this, curiosity helps the curious mind build empathy, as learning about others’ lived experiences is crucial to understanding what being in other people’s shoes might entail. From hearing about personal concerns and relating them to one’s own experiences, curiosity probes the seemingly routine attitudes that affect people’s lives and encourages everyone to re-examine their impact.

After all, small actions can have great impacts—and that applies to both negative and positive interactions. Empathy requires the curious person to wonder what someone’s day looks like and what impact their own behavior might have on their life, reflecting on what they have done wrong and on what they have done right. Curiosity, when applied to empathy, is about recognizing how we impact others and if there is anything we should change—or continue doing!

Be Brave and Ask Questions

Ultimately, curiosity demands a lot of bravery but offers a high reward. Just like it did for me at TIFF, or for Rosalind Franklin in London, it paves a path for researchers to follow. Curiosity encourages us to ask the big questions and bravely choose what to explore next. It can lead us to new discoveries and successfully transform our immediate environment. Curiosity encourages us to approach other people with openness and a willingness to learn about their unique experiences. Small questions can go a long way!

0 comments on “The Courage to be Curious”