Our land acknowledgements series highlights important stories and teachings from each of the Redefining Traditional team members – Heather, Shamim and Kaitlyn. Through these posts, we aim for our community to think about how land acknowledgments are immensely important, and to ensure we engage in teachings about specific cultures beyond a day or month of recognition. We also highlight important questions to support our community so that an acknowledgement moves beyond a ‘script’ and towards an ongoing conversation.

Our first installation is by Heather Watts!

Many school districts in Canada have recognized November as Indigenous Education Month. In the United States, November is Native Heritage Month. As an educator with a commitment to social justice and equity, teaching about specific cultures within recognition months only is extremely problematic. As a parent, I am also very cognizant about this approach at home. We are, after all, our children’s first teachers. Nonetheless, recognition months can be used as an entry point to learn more about groups of people we may not know much about, and ask ourselves why that may be.

Let’s try an exercise.

Close your eyes. What is the earliest memory you have learning about Indigenous people? Where were you? How old were you? How did this learning experience make you feel?

When I have gone through this exercise with non-Indigenous educators, I have heard responses such as:

- University was the first time I learned about Indigenous peoples; I don’t remember learning about anything in elementary school

- I learned about Indigenous peoples by first watching Pocahontas

- I learned about Indigenous peoples from watching news stories focused on land claims

Where do people learn about Indigenous people?

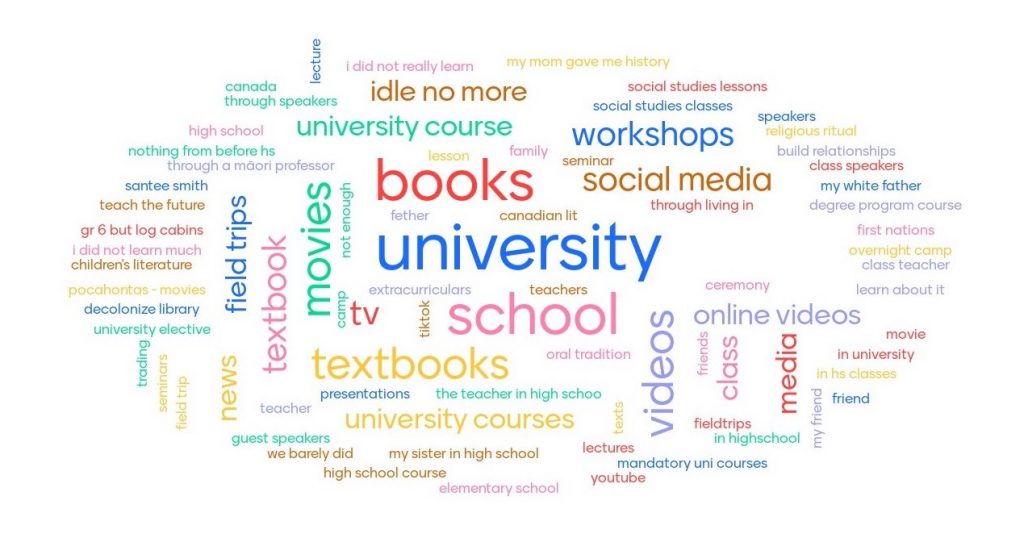

When I asked how people learned about Indigenous people in their home, school, or community – the word cloud below illustrations the most common answers. Larger words means that lots of people answered with that keyword, while smaller words means that these answers were not as common.

Of course, there are positive learning experiences I can throw in the mix here, too such as: one of my good friends is Indigenous and has taught me a lot about her culture; I have read books such as Thomas King’s The Inconvenient Indian; we went on a field trip in middle school to a residential school and learned from survivors. I should note, that these experiences were few and far in between, and were no way in balance with some of the more problematic learning experiences.

So, how do we remedy this? How do we create learning experiences for our children that work to centre Indigenous knowledges and histories in meaningful ways that are not appropriative? One entry point is to do the work of crafting a personal land acknowledgement. Below, I share an example of a land acknowledgement I wrote and delivered in February 2020 for the Black Faculty in Conversation event at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto.

She:kon, sewakwe:kon. Kahenta:ke ne yonkyahts. Kanyenkeha’ka ni:i. Waskware:wake. Good Afternoon, everyone. My name is Kahenta:ke, which loosely translated, means ‘she is in the meadow’, in Kanyenkeha, the Mohawk language. I am a Haudenosaunee woman from Six Nations of the Grand River Territory, and also have family ties to the Mississaugas of the Credit First Nation.

First, I’d like to begin by saying nya:wenkowa, thank you to our Equity Committee for asking me to lead you all through a land acknowledgement today. As Dr. Ann Lopez says, our committee is not just working to talk about equity, but to be about equity. I’d like to honour that sentiment by not reading the University of Toronto land acknowledgement, but instead personalize my honoring of these lands we walk on.

I think about these lands each and every day. Before I step foot out of my apartment, while walking my son to school, while here at OISE. I think about the Huron-Wendat people, the Haudenosaunee, and the Mississaugas of the Credit River people. I think about my ancestors taking steps on the same soil as me, and young children playing on the same grasses as my son. I think about the genius of our people. Our ways of knowing. Our systems of education. Our forms of government. Our medicines. Most importantly, I think about the fact that we are still here.

You see, when we speak of Indigenous people in the past tense, it can sometimes be interpreted that all the struggles faced were in the past tense as well. The stories of Tina Fontaine, Colton Boushie, and the current atrocities at Wet’suweten tell us otherwise. It is easier to deny Indigenous people rights if we historicize these struggles and simply pretend that we do not exist.

Land acknowledgements are not action – they are as their name suggests, acknowledgements. But, they can and should awaken something inside us that calls us to action. Long ago, treaties were agreed upon on these very lands. Treaties of shared responsibility and peace. We are all implicated in these treaties, as they are the agreements of these lands. We are all treaty people.

Where to Start:

How can we begin to craft personal, meaningful land acknowledgements in our homes, as an entry point to learn about Indigenous knowledges and histories?

- A great place to start is to become aware of the traditional territory you are currently on. Check it out here: www.native-land.ca.

- What are the impacts of colonialism here? How are these impacts still be felt in the modern day?

- Reflect on your own history in relation to the land you are on. What brought you to these lands? How did you come to be here?

- What are your own gaps in knowledge? What commitments might you make to learning more/unlearning?

As I said in my land acknowledgement for the Black Faculty in Conversation event, a meaningful land acknowledgement should call us into action, and affect the way we move on these lands. We can’t get that from scripted land acknowledgements that have been posted on our company’s shared computer drive; we must engage in our own reflections and have those show up in our own acknowledgements.

1 comment on “The Importance of Meaningful Land Acknowledgements”